Abstract

Inadequate coordination is one of the major barriers to effective intervention in to the growing drug menace. Effective coordination of stakeholders is key to success in the implementation of anti-drug policies. This paper presents the network governance model as a means of highlighting the importance of coordination in the fight against drugs. The paper focuses on two research objectives: to describe the official coordination systems employed in different countries, and to provide recommendations to strengthen the coordination mechanism for drug strategy formulation and implementation globally and locally based on theoretical framework and best international practices. To this aim, a two-staged process of literature and document research on official documents and open sources was conducted. Unique examples from national coordination systems of different countries (Türkiye, United Kingdom, France, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Portugal) as reported to EMCDDA which are employed for fight with drugs in developing and implementing strategies for increasing policy performance were reviewed. The paper finalizes with various international practices based of which recommendations are made in an effort to contribute to strengthen the national coordination system in Northern Cyprus.

Keywords: National coordination mechanisms, Northern Cyprus, network governance, anti-drug policy

Introduction

Organized crime constitutes an indisputable strategic dilemma (Cornolli, 2018) which might be mitigated by better coordination among the various authorities and agencies dealing with countering organised crime. Coordination is inherent in any management task such as planning, organizing, staffing, and control, and is an especially critical component for a successful anti-drug policy (EMCDDA, 2002). Coordination can be defined as synchronizing tasks to achieve a common and shared goal. Coordination activities encompass the generation of consensus regarding priority strategies, resource allocation, evaluation, and plans, as well as the coordinated execution of policies across various sectors of government (Hughes et al., 2013). However, many countries face significant challenges to coordinate policies related to the fight against drugs at the national level. Nearly every country has set up a national coordination system; nonetheless, their effectiveness is questionable due to the given turmoil of the environment and complex structure of the fight process. All arrangements might amount to a reallocation of resources in the execution and prioritization of needs. Any kind of decision made at the top may require legitimization at the political level.

Empirical and descriptive information on national coordination systems is critical to make a comparison. Such information can comprise country reports, which are officially submitted to the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) or EMCDDA’s general themed reports. While these are limited in number (Gärtner et al., 2011; Hughes et al., 2013; Kassim et al., 2001; Narenjiha et al., 2015) they are nevertheless valuable in academic literature.

This paper presents a review of national coordination systems obtained from open sources of different states to contribute to the development of a system in Northern Cyprus. However, this paper did not focus on the degree of interaction among stakeholders, which might be addressed in follow-up research. The paper focuses on two research obejctives: first, a theoretical interest in understanding which national coordination systems can be employed the fight against drugs; and second, a practical interest in what factors should be employed to strengthen the actual system in the Northern Cyprus. The paper was developed using a two-stage review of literature and document research.

The conceptual framework on which this paper is premised comprises an overview of coordination and its relation with network governance where findings from international implementation are presented. Official coordination systems of different countries (Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Türkiye, United Kingdom, France, Finland, Germany, and Portugal) as reported to EMCDDA which are employed in the fight against drugs in developing and implementing strategies for increasing policy performance are reviewed. The paper ends by providing recommendations based on various international practices in an effort to contribute to strengthening the national coordination system in the Northern Cyprus.

In this way, this paper attempts to enhance our overall comprehension of national coordination and serves as a convenient departure point for future research.

Problem Statement and Research Questions

The following research questions are addressed in this paper.

- Which coordination systems published on official open sources are employed in different countries in the fight against drugs as officially reported to European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA); and

- What best practises can be employed to strengthen the coordination mechanism for drug strategy formulation and implementation in the Northern Cyprus?

Research Methods

The paper was developed by conducting a two-stage content analysis of academic literature, official documents and open resources of the relevant documents from different countries. The documents search was initiated and proscribed by using keywords to delimit the search so that only those documents which contain the data focusing on the research objectives were assigned for analysis.

Contextual Framework

Definition of Coordination and Its Relationship with Network Governance

According to the Cambridge dictionary (n.d.) ‘coordination’ refers to the process of organizing the different activities or people involved in something so that they work together effectively. Coordination finds itself at the core of governance literature. Governance applies to all aspects of policy making: issues identification, policy analysis, decision-making, implementation and evaluation (Althaus et al., 2007). Coordination is critical because networks have come to dominate public policy as Peters and Pierre (1998) have reiterated the importance of coordination among these networks. This process is new in which the state does not become ineffective, but moves towards 'creating influence' on the basis of 'relative equality' with stakeholders instead of 'direct control'. Public and private sector resources are 'blended', and the state does not neglect the 'use of multiple tools' instead of using only limited tools in policy processes. This is referred to as governance model or theory (Peters & Pierre, 1998).

According to the network governance model, actors are mutually dependent on reaching objectives which create sustainable relationships between actors. This, at the same time, creates some veto power for various actors. The sustainability of interactions creates and solidifies a distribution of resources between actors. In the course of interactions, rules are formed and solidified where policy processes regulate actor behaviour. Resource distribution and rule formation lead to a certain closeness of networks for external actors (Klijn & Koppenjan, 2000).

In the current era, decision making has shifted from top-down hierarchies to negotiation amongst networks of inter-dependent players, each of whom brings their own interests and intra-organisational constraints (Börzel, 1998; Lewis, 2011). In this context of multiple policy actors and networked governance, successful coordination becomes even more critical. A comprehensive approach to studying coordination involves the identification of the actors (and missing actors); power relations and distribution of interests and resources; the formal and informal structures and their formation and dissolution; the nature of the linkages and interdependencies between actors and structures; and the dimensions of perceived ‘good’ coordination that are held by stakeholders (Hughes et al., 2013).

Importance and Role of Coordination in the Fight Against Illicit Drugs

Coordination is essential and inherent in all management functions. Specifically, it can prevent misunderstandings and thus, facilitate the development of common understanding, eliminate conflicting and probably wasteful duplications, enhance the capacity for better responses to complex problems and increase the legitimacy of outcomes (Hunt, 2005; Management Advisory Committee, 2004; Peters, 1998). Despite both the need for (and risks from poorly designed) drug policy coordination, what coordination means and how we assess the process, outputs and outcomes, or what contributes towards ‘good’ drug policy coordination is seldom defined (Hughes et al., 2013).

By analogy, we can assume that drug coordination arrangements could be interpreted as: ‘the task to organise or integrate the diverse elements composing the national response to drugs with the objective to harmonise the work’ (EMCDDA, 2001), and implicitly to increase the effectiveness. The definition of anti-drug coordination necessitates that all stakeholders involved in anti-drug policy implementation, including) both public and private entities, work towards a shared aim outlined in a plan or a common vision (EMCDDA, 2001).

Besides being a public health problem, drugs have a criminal dimension. Successfully addressing and countering the world drug problem requires close cooperation and coordination among domestic authorities at all levels, particularly in the health, education, justice and law enforcement sectors, taking into account their respective areas of competence under national legislation (UNODC, 2019). All domestic and international anti-drug authorities form a network governance model which needs due diligence.

In this respect, inadequate coordination is one of the major barriers to effective intervention, and may cause otherwise well-conceived policies to under-perform (Gärtner et al., 2011).

Coordination Models and Specific Features

Effective and efficient coordination systems are essential for reaching pre-determined goals, ensuring stability and cost reduction, especially in turbulent conditions, especially in the case of illicit drug production and trade. It is also true for preventing illicit drug abuse/misuse.

Coordination systems play a vital role in facilitating cross-unit coordination and enhancing the overall performance and efficiency of complex systems. In 1987, during the United Nations International Conference on Drug Abuse and Illicit Drug Trafficking in Vienna, it was officially recognized that there is a need to build national coordination mechanisms to effectively coordinate well-rounded national anti-drug programmes. Any national coordination system needs to have a structure and access to resources and tools (data and analysis, decision-makers, finances, etc.) that are appropriately matched to the type of drug issues it is tasked with responding to (EMCDDA, 2017). There are several anti-drug models used in different countries, which can be classified into i) Specific Domain Coordination ii) Horizontal Holistic Coordination.

Specific Domain Coordination

In this model, in contrast to the holistic model below, the coordination body is situated under the jurisdiction of a minister who is responsible for overseeing and executing the operations pertaining to its specific areas of expertise. This function can be either vertical, focusing on activities within the ministry's specific field, or horizontal, encompassing activities across multiple ministries. It can also encompass varying levels of decision-making authority.

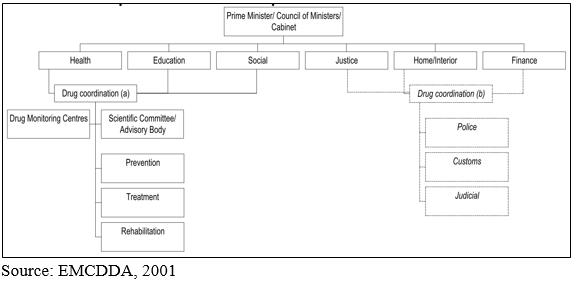

A classic example is the Health Ministry, which assumes responsibility for the coordination and implementation of preventive, therapeutic, and rehabilitative measures, coordinates the overall activities in these fields of other administrations such as the Ministries of Social Affairs, Education, Youth, etc. (see Drug coordination part (a) of Figure 1 Specific Domain Coordination). Activities coming under other domains such as Justice, Home/Interior, Customs, Finance are, at first analysis, normally not within the scope of this model. However, some coordination systems, even if located within the Ministry of Health, do encompass some activities falling under the general scope of Justice or Interior Ministries (EMCDDA, 2001).

Countries may also have separate coordination arrangements for linking only law-enforcement activities (Drug coordination part (b) of Figure 1) In Finland, for instance, the primary responsibility for coordinating national anti-drug policy lies with the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. The ‘Coordination Group’, appointed in 1999 with representation from Ministries and state agencies, aims to harmonise anti-drug policy and to intensify collaboration between the authorities in their efforts to implement the national anti-drug strategy. Important institutions are the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) which is an independent state-owned expert and research institute that promotes the welfare, health and safety of the population. They operate in the administrative branch of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. THL’s duties are established in the Finnish legislation. Its key duty is to carry out research and use its expertise to prevent illnesses and social problems, develop the welfare society and support the social welfare and health care system, and the social security system. It produces information and solutions for stakeholders, decision-makers in central government, municipalities, and wellbeing services counties and local government officials’ social welfare and health care professionals. Moreover, it maintains statistics and registers and functions as a statistical authority (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare , 2024).

Likewise, in Germany, the Federal Government Commissioner for Drug Issues (Bundesdrogenbeauftragte/r) nominated in January 2001, is responsible for coordinating the federal government's drug policy, health and social aspects promoting and coordinating harm reduction and anti-addiction policies. In Germany, the Commissioner's remit includes: developing strategies and measures to prevent drug abuse and reduce drug-related harm; coordinating drug policies at the federal level and working with state governments, local authorities, and stakeholders; advising the government on drug policy issues and representing Germany in international drug policy forums, supporting research and evaluation to inform drug policy decisions and raising public awareness about drug-related issues and promoting drug education and prevention programs. The Commissioner works closely with various ministries, agencies, and organizations involved in drug policy to implement these responsibilities (Bundesdrogenbeauftragter, 2024). The Commissioner also deals with international relations. Public order and judicial issues on drugs remain within the Ministries of the Interior, Justice, and the Land Ministries and customs authorities which operate across borders. In almost all Länder (states of federal Germany) interministerial work-groups coordinate the activities of the different administrations (health, social, youth, culture, interior and justice) (EMCDDA, 2001).

When compared to the horizontal holistic model below, it is interesting to note that when the authority responsible for 'overall' coordination is located in one of the ministries, that ministry holds the overall responsibility of coordination. While this ministry may possess authority to coordinate and make decisions within its own domain, it merely serves as a forum for discourse (without decision-making power) regarding issues that are the purview of other ministries (EMCDDA, 2001).

Horizontal Holistic Coordination

This is the model preferred by many countries including Republic of Türkiye and Northern Cyprus, ensuring that all government agencies, ministries, and departments operating in the field are involved in the pursuit of common goals for the fight against drugs. This entire unit is responsible for monitoring drug-related policies and initiatives. Experts from many institutions come together to develop and coordinate all the actions and main strategies of the government (Narenjiha et al., 2015).

This model incorporates a centralized coordinating system founded on a comprehensive approach and a hierarchical decision-making authority that is centrally focused. The coordination office would be responsible for establishing horizontal and vertical connections between the national and local authorities. The scope of this task may encompass programming, overseeing the execution, and conducting assessments which is the typical of interministerial bodies with decision-making powers. Budget and legislative orientation might also be located here (EMCDDA, 2001). A national strategy document and action plan and/or an official drug policy provides a clear outline of the national course of action, led by the horizontal holistic coordination unit. An action plan, strategy, or formal drug policy typically provides a clear outline of the intended course of action. All operations carried out by various governmental units, NGOs, and private sector firms adhere to the established plan and are subject to the oversight of the holistic coordination authority.

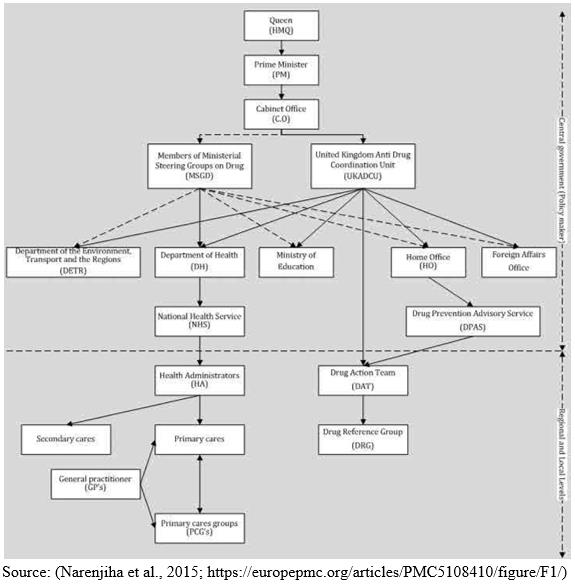

In 1998, the United Kingdom implemented a coordination system (see Figure 2 below) where the prime minister appointed a national coordinator responsible for organizing a comprehensive national strategy on drugs. This fostered collaboration among government departments, agencies, and other stakeholders to collectively achieved common goals.

The bidirectional relationship between these institutions and government agencies within the anti-drug structure in the United Kingdom enables policy makers to gain a comprehensive understanding of the demands and perspectives of the community which allows them to develop policies and strategies that serve as benchmarks for institutions involved in addiction-related activities and objectives (Narenjiha et al., 2015).

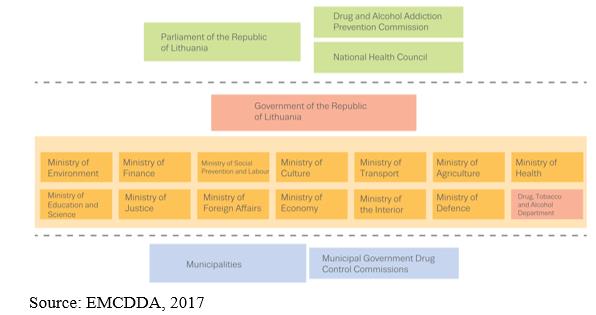

Horizontal holistic coordination units may operate differently in federal and unitary states. The coordination system in Lithuania, which is a unitary state, is presented here in Figure 3.

France employs a similar coordination structure known as the French Inter-ministerial Mission for Combating Drugs and Addictive Behaviours (MILDECA). Over time, MILDECA has expanded its scope to encompass addictive behaviours such as gambling and gaming, in addition to consumption of illicit substances, alcohol, tobacco, medications, and doping (MILDECA, 2024). It also plays a crucial role in monitoring, assessing, and preventing potential or proven medication risks, thereby ensuring the safe use of medicinal products after marketing to protect public health in France. The national plan in France focusses on mobilisation against addictions including alcohol, tobacco, drugs and screens (MILDECA, 2018).

Despite a few exceptions, Portugal serves as another illustration of this type. Political and technical coordination are separated, and Prime Minister (or their Secretary of State) chairs the Coordination Board of the National Strategy which holds the ultimate political authority to make final decisions. The technical level is handled by the Portuguese Institute for Drugs and Drug Addiction (IPDT) for prevention and treatment, and its role includes coordinating the execution of the national policy. The Board manages the government's strategy in the four areas specified under the National Drug Strategy: prevention, combating drug trafficking and associated criminal activities, treatment, and rehabilitation (Portuguese Institute for Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2024).

In Portugal, in 2002, the Institute of Drugs and Drug Addiction (IDT) was established by merging the Service for the Prevention and Treatment of Drugs and Drug Addiction (SPTT) and the Portuguese Institute of Drugs and Drug Addiction (IPDT) (2024). In 2010, the organization restructured its coordination mechanisms to address the issue of drug abuse and addiction. Additionally, it enhanced its authority in defining and implementing rules related to the harmful use of alcohol. Its remit includes: research and monitoring, prevention, treatment, training and education and international cooperation. Overall, the IPDT plays a vital role in executing Portugal's drug policy, which is recognized for its emphasis on public health and harm reduction instead of criminalization.

Leadership in Coordination Models

The formulation and approval of national drug policy frequently falls under the responsibility of ministers who oversee significant governmental domains. However, it can also be a unit operating under the Council of ministers which is the case in Bulgaria where the National Drugs Council is chaired by the Minister for Health, with two Deputy Chairman (the Chief Secretary of the Ministry of Interior and a Deputy Minister of Justice), secretary and members. Besides representatives of related Ministries, members of the President of the Republic of Bulgaria, the Supreme Court of Cassation, the Supreme Administrative Court, the National Investigation Office and other institutions (Bulgaria National Focal Point on Drugs and Drug Addiction, 2021) are members of the council.

National-level frameworks exhibit significant variation across different countries. Occasionally, the prime minister can serve as the leader of the governing body, as seen in countries such as Latvia, France, and the Czech Republic. In Latvia, the national coordination unit is known as the Drug Control and Drug Addiction Restriction Coordination Council, which is chaired by the prime minister and concerned ministries but not representatives from judicial authorities like in Bulgaria. There are also several national expert members to contribute to the Council (EMCDDA, 2019; Czech Drug Policy, 2024).

In 17 European countries, these structures are attached to the ministry of health (or its equivalent), while the remainder are connected to the ministry of the interior, justice, family or social affairs or, in some cases, directly to the Prime Minister’s Office/Office of the Government such as in the Czech Republic (EMCDDA, 2011; Czech Drug Policy, 2024). In the case when a minister is not directly responsible for the drug strategy, a dedicated national coordinator is assigned.

In Portugal, part of the Ministry of Health, Director General of the General-Directorate for Intervention on Addictive Behaviours and Dependencies (SICAD), serves as the National Coordinator for Drugs, Drug Addiction, and Alcohol-Related Problems. In sum, when a minister is not assigned, such coordinator roles are borne by senior public servants familiar with the area. They are responsible for driving the strategy’s overall implementation and working with stakeholders at all levels.

In many cases, the national drug coordinator chairs and manages either the ministerial or the operational coordination structures. For example, in Luxembourg, the Inter-ministerial Commission on Drugs is chaired by the National Drug Coordinator and is appointed by the Minister for Health (EMCDDA, 2011; IPDT, 2024).

Findings

It is widely acknowledged that coordination is a cornerstone of effective drugs policy (EMCDDA, 2003). The activities (to be coordinated) must follow a plan in which objectives and targets are defined in quality, quantity and time frame. All the actors involved in the delivery of the results at national, but especially at regional and local level are interlinked, know the plan and work for its implementation (EMCDDA, 2011).

The national coordination mechanisms operate at vertical and horizontal level, and are supported by regional and local levels and with technical committees. The drug coordination arrangements and structures are varied due to historic legacies, legal framework, cultural and political contexts and hence regarding interactions, there is no “one best way of doing things” and “an ideal coordination model”. Any state can choose from a variety of coordination systems depending on domestic arrangements, administrative culture, political power balances and historical legacies, without one being necessarily superior to the other in terms of political effectiveness (Gärtner et al., 2011). Nevertheless, the specific characteristics noted earlier indicate that certain coordination models may be structurally better suited for the specific circumstances of a given state and time than others. Regardless of the coordination system being specific domain model or horizontal holistic coordination model, the degree to which the central coordination mechanism/unit remains actually superior to the corresponding units in the respective line ministries (EMCDDA, 2001) bears importance.

There are several challenges of coordination, including but not limited to ensuring effectiveness, sustaining coordination as conditions change, assessing it precisely (Hughes et al., 2013), and using resources efficiently. Also, the term ‘coordination’ is elusive. For instance, despite the numerous references to the expressions such as ‘provide’, ‘facilitate’, or ‘improve’ coordination, many drug strategy documents provide no definition of what this entails (Office of National Drug Control Policy, 2010 as cited in Hughes et al., 2013). In that sense, the coordination role of any unit should include what to do and also what not to do and measurable outcomes should be preferred when defining tasks.

Another important point is that effective coordination at the horizontal level is as important as the vertical dimension for turmoil environments. This gains critical importance when urgent response is needed, which necessitates fewer communication channels to be followed. The coherence of the coordinating system is closely linked to the presence of specific criteria, such as national leadership at both the political and operational levels in all sectors impacted by the drug phenomena (EMCDDA, 2011).

Specifications of an effective antidrug coordination system include its capacity to provide evidence-based information. In that sense, advisory groups such as scientific committees need to be developed and sustained. Drug monitoring systems are essential components for supplying evidence-based information to central coordination mechanisms (EMCDDA, 2011).

The noteworthy finding in several countries is the importance given to research and monitoring activities. In Portugal, the national coordination mechanism (IPDT) emphasizes the research and monitoring role. Conducting research on drugs and drug addiction trends, as well as monitoring the effectiveness of drug policies and interventions are of high priority which are essential for a more effective departure point for coordinating the specific purposes the drug policy is dedicated to.

Maintaining statistical data and keeping registers nationwide is also a critical task for a sound anti- policy. In Finland, there is a similar case where the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos -THL) serves as an official statistical unit performing this task. THL enables the provision of forensic medicine, and social and health care services on behalf of the state as well as directing the national information management for social welfare and health care services (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, 2024).

Structure is important, and can facilitate coordination, but to produce behavioural changes may require the active intervention of political leaders; often political leaders at the very top of the government (Peters, 1998). The leadership for anti-drug coordination has also vital importance, which is closely related to the hierarchical level whereby the chair of drug coordination unit is situated in the overall organizational chart. Although this is related to the local administrative culture and practices, leadership at lower levels like Department Heads might not signal low importance necessarily. Nonetheless, optimal attainment might signal the importance attributed to the anti-drug policy for most countries. This is also true for Republic of Türkiye, where the Higher Board for the Fight against Addiction is chaired by the Vice President, or in Portugal, which is led by Prime Minister, thereby placing the role of coordination very high on the political agenda. The existence of a ‘white paper’, ‘political note’, ‘drug strategy document’, or ‘action plan’ in which the objectives and directions of the national drug policy; the participation and or involvement of all actors, public and private, concerned with the drugs problem in all fields are clearly stated; thus highlighting the significance of ‘working together towards a common objective’ and the role of evidence-based information providers as a vital factor in the decision-making process (EMCDDA, 2001).

Conclusion

Studies on many countries suggest there is no “ideal coordination model” which produces the best policy outcomes. Effective coordination of anti-drug policies requires a system capable of vertical and horizontal coordination linking local, national and international levels. The level of ministerial or higher engagement in drug policy reforms is contingent upon many contextual conditions.

Nevertheless, there exist certain specific domestic challenges that could hinder the smooth coordination and successful collaboration in the process of policy-making and implementation. These include firstly, inadequate leadership, and inadequate coordination between vertical and horizontal dimensions. Secondly, and strongly connected to this, is the vital importance of degree of collaboration between units. It is assumed that coordination and collaboration go hand-in-hand, and cooperation is assumed to be provided in any case. However, this may not be happen in a timely fashion and at the needed ratio, which impedes coordination.

Regarding national coordination, the horizontal holistic approach and specific domain coordination can be employed by countries, regardless of the drug policy whether it is focused on harm reduction or a drug free society.

The degree of supremacy of the central coordinating unit/body over the related units, either ministries or other agencies, varies significantly from one country to another.

Recommendations for the Northern Cyprus

There is no ideal model for coordination, and each country selects one which is aligned to its cultural, historical, and administrative roots. The coordination model that Northern Cyprus applies is the holistic horizontal model which is implemented in many countries. The hierarchical level is high and is bound to the Prime Minister’s office encompassing other Ministries and relevant bodies. Salient points of concern for the Northern Cyprus can be summarized as follows:

Firstly, joint focus on different dimensions of addiction can be combined in one higher coordination mechanism, as was vitalized in Portugal back in 2010. Also in France, mobilisation against addictions including alcohol, tobacco, drugs and screens was tackled in the same national coordination body (MILDECA, 2018). In the Czech Republic, drugs, alcohol, tobacco and gambling problems are dealt with in an integrated manner (Czech Drug Policy, 2024). It is even more comprehensive in Türkiye, with alcohol, drugs, tobacco and behavioural addictions dealt with by the Higher Board for Fight with Addiction (Bağımlılık ile Mücadele ile İlgili 2019/2 Sayılı Cumhurbaşkanlığı Genelgesi, 2019). More than one addiction or abuse issues can be dealt with in a single coordination model.

Secondly, coordination in the fight against drugs should be implemented and institutionalized at every stage, in the form of internal (vertical and horizontal), external (inter-institutional) and procedural coordination. Although vertical coordination is relatively easier to achieve both within and between institutions, the key to responding on-site by adapting to changing situations in the fight against drugs is to ensure effective inter-institutional horizontal coordination. This needs to be defined to increase efficiency and decrease time consumed.

Thirdly, for effective coordination, it is vitally important to clarify the relationship between key actors at the policy level, strategy level and operational level for effective inter-institutional coordination, which can sometimes become a difficult goal to achieve and maintain.

Fourthly, all the abovementioned issues in the legal framework will benefit all parties as it is the case in Northern Cyprus. However, there are some elements of coordination in anti-drug strategies that should be included in the legislation. These include the abundance of buffering resources (money, human resources and time), the effective use of information systems, and the establishment of lateral relationship networks since the drug environmental factors are complex and dynamic.

Fifthly, is the need to implement anti-drug strategies together with international actors because of the constant renewal of the types of drugs trafficked and ways of use requires countries to work together in unity and coordination.

Sixthly, the factor that largely determines the success of the fight against drugs is that the process of crafting multi-actor and multi-layered strategies. It is expected that in the fight against drugs, the process and methods of fighting against drug supply will be limited to only the relevant layers and actors due to their confidentiality in the context of security. In remaining processes, progress with the contributions of all relevant actors in the development and implementation of the strategy has a key role in terms of ensuring the continuity of the struggle as well as its internalization and dissemination of the all out struggle.

Declaration of Conflicts Interests

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

Althaus, C., Bridgman, P., & Davis, G. (2007). The Australian Policy Handbook (4th ed.). Allen and Unwin.

Börzel, T. A. (1998). Organizing Babylon: On the different conceptions of policy networks. Public Administration, 76(2), 253–273. DOI:

Bağımlılık ile Mücadele ile İlgili 2019/2 Sayılı Cumhurbaşkanlığı Genelgesi. (2019, February 14). T.C. Resmi Gazete (30686, 14 February 2019). https://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2019/02/20190214-12.pdf

Bulgaria National Focal Point on Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2021, December 23). National Drugs Council. https://www.nfp-drugs.bg/en/the-national-drugs-council

Bundesdrogenbeauftragter. (2024, February 1). Beauftragter der Bundesregierung für Sucht- und Drogenfragen. https://www.bundesdrogenbeauftragter.de/beauftragter/

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Coordination. In Cambridge Dictionary.com dictionary. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/coordination

Cornolli, V. (2018). Back Matter (Concluding Chapter). In V. Cornolli (Ed.), Organized Crime and Illicit Trade: How to Respond to this Strategic Challenge in Old and New Domains (1st edition, pp. 135-138). Palgrave Macmillan Cham. DOI:

Czech Drug Policy. (2024, February 5). Czech Drug Policy and Its Coordination Evidence-based Addiction Policy. https://vlada.gov.cz/assets/ppov/protidrogova-politika/GCDPC_information_1.pdf

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). (2001). Drug Coordination Arrangements in the EU Member States. Office for Official Publications of European Communities.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). (2002). Strategies and Coordination in the Field of Drugs in the European Union: A Descriptive Review. Office for Official Publications of European Communities. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/technical-reports/strategies-and-coordination-field-drugs-european-union-descriptive-review_en

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). (2003). Coordination: A Key Element of National and European Drug Policy. Office for Official Publications of European Communities.

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). (2017). New Developments in National Drug Strategies in Europe. Office for Official Publications of European Communities. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/emcdda-papers/new-developments-national-drug-strategies-eu_en

European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA). (2019). Latvia Country Drug Report. Office for Official Publications of European Communities. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/country-drug-reports/2019/latvia_en

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. (2014, February 2). About THL. https://thl.fi/en/about-us/about-thl

French Inter-ministerial Mission for Combating Drugs and Addictive Behaviours (MILDECA). (2018). France's National Action Plan on Addiction 2018-22. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/drugs-library/mildeca-france-2018-france’s-national-action-plan-addiction-2018-22-en-version_en

French Inter-ministerial Mission for Combating Drugs and Addictive Behaviours (MILDECA). (2024, March 10). https://www.drogues.gouv.fr/nous-connaitre

Gärtner, L., Hörner, J., & Obholzer, L. (2011). National Coordination of EU Policy: A Comparative Study of the Twelve “New” Member States. Journal of Contemporary European Research, 7(1), 77-100. http://www.jcer.net/ojs/index.php/jcer/article/view/275/261

Hughes, C. E., Ritter, A., & Mabbitt, N. (2013). Drug policy coordination: Identifying and assessing dimensions of coordination. International Journal of Drug Policy, 24(3), 244-250. DOI:

Hunt, S. (2005). Whole-of-Government: Does working together work? Asia Pacific School of Economics and Government, The Australian National University.

Kassim, H., Menon, A., Peters, G. B., & Wright, V. (Eds.). (2001). The National Co-ordination of EU Policy: the European Level. Oxford University Press. DOI:

Klijn, E. H., & Koppenjan, J. F. M. (2000). Public Management and Policy Networks: Foundations of a network approach to governance. Public Management: An International Journal of Research and Theory, 2(2), 135–158. DOI:

Lewis, J. M. (2011). The Future of Network Governance Research: Strength in Diversity and Synthesis. Public Administration, 89(4), 1221-1234.

Management Advisory Committee (MAC). (2004). Connecting Government: Whole of Government Responses to Australia’s Priority Challenges. Australian Public Service Commission

Narenjiha, H., Noori, R., Ghiabi, M., & Khoddami-Vishteh, H. R. (2015). Characteristics of drug demand reduction structures in Britain and Iran. Epidemiology, biostatistics and public health, 12(1), 11173. DOI:

Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (1998). Governance without Government? Rethinking Public Administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(2), 223–243. DOI:

Peters, G. (1998). Managing Horizontal Government: The Politics of Coordination. Canadian Centre for Management Development.

Portuguese Institute for Drugs and Drug Addiction (IPDT). (2024, March 1). Structure. https://www.sicad.pt/EN/Institucional/Organograma/Paginas/default.aspx

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). (2019). Commission on Narcotic Drugs, Implementation of all International Drug Policy Commitments, Vienna. Follow-up to the 2019 Ministerial Declaration “Strengthening Our Actions at the National, Regional and International Levels to Accelerate the Implementation of Our Joint Commitments to Address and Counter the World Drug Problem”. United Nations.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 July 2024

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-625-98059-0-0

Publisher

Emanate Publishing House Ltd.

Volume

1

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-114

Subjects

Addiction, addiction recovery treatment, prevention, drug use, workplace drug testing, toxicological analyzes

Cite this article as:

Kiliç Akinci, S. (2024). National Drug Policy Coordination: A Key Element of Success. In K. Ögel (Ed.), Effective Drug Control Strategies in Northern Cyprus: Challenges and Opportunities in 2024, vol 1. Emanate - Highlights from the Drug Abuse and Addiction Studies Sessions (pp. 34-47). Emanate Publishing House Ltd.. https://doi.org/10.70020/ehass.2024.7.5